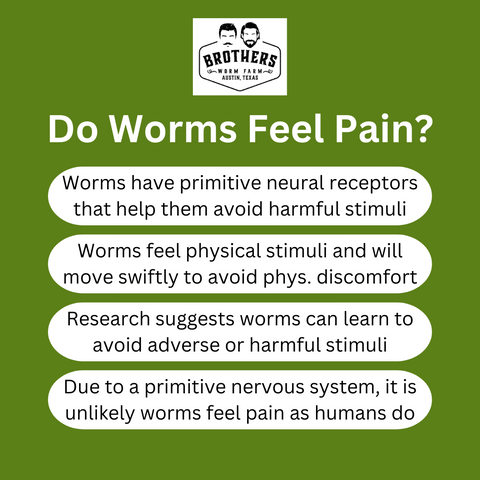

Do Worms Feel Pain?

It's a question that might worm its way into your thoughts as you watch red wigglers twist their way through the mud after a rainstorm: do worms feel pain?

While these simple animals lack complex facial expressions to convey discomfort, worms are more than just wriggling soil-dwellers.

For the longest time, since humans learned that sticking these creatures on a hook and bobbing them in the water could lure fish, it was thought that worms and other such invertebrates could not feel pain—at least not in the way that humans can.

But does their inability to process pain the same as humans truly mean they cannot feel pain?

Recent scientific inquiries have shed light on the surprisingly intricate world of worm biology, challenging long-held assumptions about what these creatures can feel.

Do Worms Feel Pain: What Science Says

A study from Northwestern University found that flatworms possess receptors that respond to noxious stimuli like scalding heat and dangerous chemicals. This discovery points to a deep-rooted evolutionary trait, suggesting a form of pain or sensation detection in earthworms. More specifically, the study shows that worms have receptors, similar to those in humans and other mammals, that are highly sensitive and help the worms avoid or respond to environmental hazards.

When faced with dangerous external stimuli, worms exhibit behaviors that indicate a cellular awareness of potential harmful conditions.

However, these receptors alone do not prove that worms have specific feelings of pain the way humans do.

Do Worms Feel Pain When Hooked?

Based on current research it is likely that worms feel sensations, but not necessarily pain in the human sense when hooked. Worms have nerve cells tuned to various damaging stimuli, from chemical and electric shocks to being poked with a fishing hook. Experiments have revealed that worms don't just squirm randomly when exposed to adverse conditions - the worms engage in swift behaviors to mitigate or avoid the discomfort, suggesting the worms sense or feel sensations they want to avoid.

For instance, administering acidic substances prompts worms to move away, a consistent response that suggests a level of nociceptive capability—the ability to detect and react to painful encounters.

Further research supports this, showing that worms respond to electric shocks with swift avoidance maneuvers. These reactions are not merely reflexive twitches but are considered efforts to escape the source of harm.

This consistency in behavior across different forms of stimuli supports the idea that worms may indeed experience a sensation of stimuli they want to avoid, although the experience is more primitive than the emotional or physical pain felt by humans or other mammals.

Do Worms Feel Pain When Cut?

Studies have shown that worms possess receptors and neurons that alert the worms to harmful conditions, and that worms will react to avoid harmful stimuli like being cut. Science and simple observation when cutting a worm suggest that worm reactions are not just involuntary spasms but coordinated movements designed to avoid potential harm. So although worms may not feel pain when cut in the same way humans do, evidence suggests that worms do feel sensations and will move to avoid those that are harmful.

Although worms can respond to physical damage, such as being cut, through reflexive protective behaviors, it is not clear they experience pain as humans do. Research has shown that worms lack the complex brain structures necessary for the conscious experience of pain.

Worm response to harmful stimuli is likely “nociceptive” rather than indicative of pain perception, meaning their response to harmful stimuli is an automatic biological reaction rather than a subjective experience of suffering.

Can Worms Learn to Avoid Harm?

Evidence suggests that worms and other primitive organisms can exhibit learned avoidance behaviors after repeated exposure to adverse stimuli. This capability extends beyond immediate reflex actions and into behavioral adaptation over time.

For example, a study by researchers at the Department of Biology at MIT found that nematodes could learn to avoid pathogenic bacteria after a harmful encounter, indicating not only a form of memory but also a form of learning that helps them steer clear of future harm.

This behavior indicates more than a simple nociceptive avoidance response; it suggests a capacity for associative learning based on negative experiences.

Another study by Matthews and colleagues further supports this notion. It demonstrated that worms could alter their behavior after being presented with a noxious stimuli, such as an aversive taste or harmful temperature, leading to an avoidance response upon subsequent exposures.

These learned behaviors are important indicators of an organism's ability to adapt to its environment and potentially imply a level of sentience that includes the capacity to modify actions based on past adverse experiences.

Such findings continue to shape our understanding of nociception and pain in invertebrate species like worms.

Do Worms Feel Pain: Frequently Asked Questions

Does it hurt worms when you pick them up?

It is unlikely that worms hurt when you pick them up. A worm's simple nervous system enables them to detect and respond to touch and stimuli, but there is no evidence to suggest that this response is accompanied by a pain perception that is experienced by more complex animals with advanced central nervous systems.

In other words, a worm's reaction to being picked up is more accurately described as a mechanical response to stimuli designed to protect it from potential threats.

Do Worms Feel Pain: Summary

While it is clear that worms react to harmful stimuli through reflex actions, the cognitive capacity required to experience pain as suffering remains a topic of debate.

The evolution of receptors to recognize dangerous conditions suggests fundamental traits emerged to help worms detect and avoid harmful stimuli in their environment, but these receptors alone do not prove that worms experience or anticipate pain in the way humans and other mammals do.